By Anonymous

A central theme in our discussions is the question: whose obligation is environmental health? Timberland is an interesting area where private capital can have a positive impact regardless of responsibility. Given attractive investment attributes, institutional money will increasingly influence sustainable forest management (“SFM”) in developing countries. Due to forests’ public-goods aspects, governments need to accelerate capital inflow with investment-enabling policies but also mandate controls to balance institutional ownership effects.

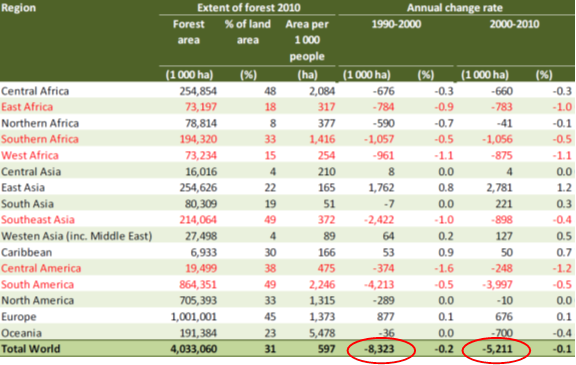

Forests cover one-third of global landmass. They are still shrinking and emitting large amounts of CO2, albeit at a lower rate than before:

Figure 1: Global Forest Cover

Source: FAO.

To achieve long-term SFM, the financing needs to be sustainable, too. Public funds are simply insufficient, not to mention governments’ relative lack of management skills, accountability, and in some cases incentives (e.g., artificially cheap fuel wood means less political trouble). Institutional funds can help overcome these issues.

From an investing perspective, timberland has several attractive characteristics:

· Low correlation with other asset classes

· Inflation hedge as a real asset

· Ability to delay harvest and let value appreciate

· Majority of returns from biomass growth (vs. land value, for example)

This makes it ideal for pension funds, endowments, and insurance companies, which comprise a large chunk of institutional money. The trend to institutional ownership has only recently started in emerging countries, and that is exactly where deforestation is highest – but so are biomass growth rates:

Figure 2: Biological Growth Rate (m3 per ha per year)

Source: Global Environment Fund.

500 million hectares of degraded land are also located there. In theory, this means that these regions are ripe for investment in SFM and plantations. Reaching zero deforestation is good; net reforestation is better.

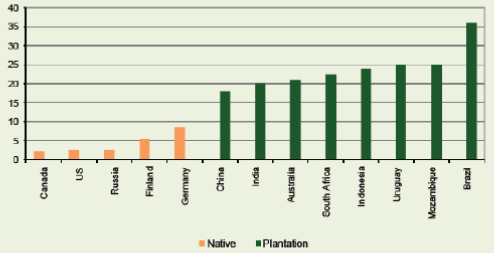

Figure 3: Reforested Formerly Degraded Land

The impact of institutional ownership could be substantial. For reputational reasons, most investors will only invest in sustainably managed forests. Increasing local employment counters small-scale logging for immediate financial gain. Professional investors also bring improved accountability, and stronger management and operational efficiency mean less strain on resources. Importantly, this owner-type actively looks for non-production revenue sources such as eco-tourism, hunting licenses, conservation easements, and, of course, carbon credits.

In practice, country governments need to be involved in the beginning, particular with existing forests. First, they need to lower capital barriers by raising the political profile to improve transparency and establishing clear resource rights. Critically, governments can help enable higher-use value. Ultimately, income from forests needs to be similar to alternatives. The role of forests as carbon sinks has rightfully received increasing attention, as deforestation accounts for one-fifth of global carbon emissions. But forests also provide bio diversity habitat, pharmaceutical ingredients/discoveries, biomass energy, prevention of desertification, and filtering and storing of clean water. Governments should offer tax breaks and other compensation in recognition of the tangible benefits forests provide to the wider public, particularly their role in soil erosion and water management. Here, institutional investors have a strong incentive to find ways to realize this hidden value.

One potential downside of private, often financial, investors owning timberland is the tendency to grow monoculture forests. These contain less biodiversity and are more vulnerable to beetle and fungi infestations. Governments could mitigate these risks by mandating alternating species on adjacent land and by following Brazil’s lead, which requires a percent of total owned forest be set aside for conservation.

Money does grow on trees, and this can benefit the environment, if balanced by sensible government policies. At the very least, high-growth plantations in emerging countries can take some pressure off natural forests.

Further Reading

SFM Fact Sheet: SFM and the Multiple Functions of Forests

http://www.cpfweb.org/32819-045ba23e53cbb67809cef3b724bef9cd0.pdf

Broadening Financial Base for SFM

September 17, 2013

September 17, 2013

I wonder if there is a similarly between the notion of “sustainable forest management” and the question we considered in the C12 case, “Can we use fossil fuels sustainably?” While planted forests serve a purpose as carbon sinks, I wonder whether promoting SFM along these lines will make it easier to rationalize the continued loss of natural forests? The value of natural topical, temperate, and boreal forests seems a lot less clear, at least on a short-and medium-term basis, than the value of tree plantations to harvest palm oil, rubber, timber, and other resources. For example, I agree that ecotourism and the promise of medical discoveries are compelling reasons not to clear forests, but these benefits seem less attractive (at least from an institutional investor’s point of view), than the more stable/recurring returns generated by planted forests (even if managed sustainably). In a world where new financial instruments are continually created to value intangible goods or uncertain future profits, I’m always amazed by our collective inability to measure the intangible benefits that intact and healthy ecosystems provide. Because of the difficulty of valuing common goods like climate regulation, clean water, and healthy soil in comparison to the defined economic benefits generated by clearing forests for fuel and other uses, societies continually choose the latter approach. An interesting case to watch is that of Borneo, where some of the last remaining tropical rainforests in SE Asia are under threat from logging, land-clearing, and conversion activities (especially for oil palm and timber plantations). Thanks for posting about this topic!

I completely agree with your view on this topic, and I’m also frustrated by the short-sightedness of immediate profits versus long-term benefits, which are very real; I think people will regret some of these decisions. The World Bank actually received a lot of criticism a few years ago for investing in palm oil plantations in South East Asia (I believe mostly Indonesia), which seemed a great way to raise locals’ income – the problem was, as you mentioned, that native forest was cleared for some of these plantations. Assessing whether land was already cleared is difficult for would-be investors. But that shouldn’t prevent capital from going into sensible forestry projects. Reputation can be powerful for fund managers who need to raise more capital again in the future, and there is a lot of degraded land available. I agree that managing existing natural forests is trickier.

A very interesting documentary on the topic of reforestation and tangible benefits is “Green Gold” by John Liu, who describes how soil erosion can be reversed, and formerly barren land turned productive for agriculture, relatively quickly by planting trees.

Regarding the pricing of public goods – a recurrent theme (and one of the fundamental issues in this course) – I am hoping that the Reinventing Capitalism class will provide some alternatives, or at least get us thinking in that direction.